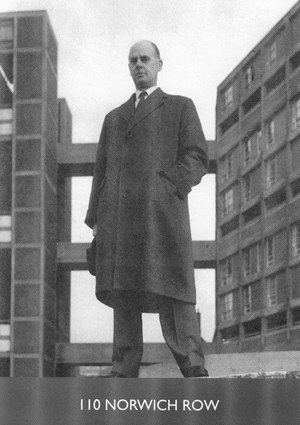

There’s a picture I know, that I keep in my head. A proud man, an architect, stands in front of a new building, in the black and white early 60s. He’s wearing a long coat, and staring straight into the camera, right back at me.

He’s not a famous architect. He doesn’t really look like a revolutionary, or a radical. But the building he’s standing in front of is both of these things. It’s called Park Hill. It’s a brutalist housing block, built on a hill overlooking the city of Sheffield, my city. And it’s a symbol of a time when this city, this provincial northern town, had a dream, had a vision. When it was a City On The Move.

In the 1950s, there were still people living in slum housing across Sheffield, unfit for human consumption. Park Hill was built to replace one of these slums. The city’s architecture department, of which this man was the head, came up with a plan: to keep the community together, to transplant whole streets of people into a state-of-the-art new building. To stack the streets on top of each other, with wide decks outside the front doors, running down to the ground. Literally building streets in the sky.

The finished building was Modernism, Brutalism, at its finest. Exposed concrete, rough brick, no adornment. Human and simple and honest. But more than the architecture, it was the ideas behind Park Hill which made it so daring, so Modern. Doing something no-one had done before, because it made sense to do it. Taking normal, hard-working people out of poverty, and creating something amazing for them, that the whole city could be proud of. The idea that Nothing Is Too Good For Ordinary People.

For a while, it worked. People came from all around the world to photograph it, to beam pictures of this building back home. Hundreds of glorious black and white images, of children playing on the decks, of young couples walking through the courtyards, arm in arm, exchanging lovely, deep Yorkshire vowels. And people loved it. There are reels and reels of interviews with the residents. A young mum with a beehive hair-do demonstrates the central heating. An old woman wearing her hair in rollers, with thick Alan Bennett glasses on, tells the camera ‘they’ve built us a paradise up here’.

The flickering film makes my heart stir. This is what architecture means to me. To think that these men, these anonymous architects, planners and politicians, did something so courageous, took such a risk. To think that this happened in my city, that my council, today so meek and dull, were so proud of this building that they produced a book in English, Russian and French, to let the world know about it.

All of this should be in a museum, to the architects, to the people who made progress possible. But somehow, somewhere along the line, Park Hill started to go wrong. The concrete didn’t wear so well in northern winters, the lifts broke down, nothing was maintained. And society began to change. The ideas behind Park Hill went out of fashion. Community was replaced with individualism, with Thatcher and Reagan and greed.

And then suddenly, in the mid 80s, people decided that Park Hill was a disaster. They heard rumours of piss in the lifts, of tellies out of windows, muggers, rapists, gangs. Unsubstantiated, but it didn’t matter. The damage was done. Park Hill was inhuman. Park Hill was Social Engineering Gone Wrong. Park Hill was a mistake.

The impact was massive. The city suffered a generation-long civic anxiety attack. The municipal architecture department was closed down. Today, the idea of our city, our council, building anything other than a bus stop brings everybody out in a rash.

And you can see the results all across the city. Sheffield is now engaged in another frenzied act of knocking down and rebuilding. But this time, the new city is completely privatized, sold off, made of luxury flats, office blocks, and new shops. Whole city streets sold to private developers for aspirational shopping schemes. We don’t dare do anything else. The consultants, the experts, tell us there’s no room for social housing, no money for new tram lines, no chance of new post offices. Our leaders don’t even have the confidence to build new public toilets. If you need a shit, you can go in John Lewis like everyone else.

And this isn’t just happening in Sheffield. It’s happening everywhere, all over the country. Today’s cities are for lawyers, footballers, and footballer’s wives. The Ordinary People are nowhere to be seen.

When I sit next to these new offices, in the shadow of the new towers, I think of that photo again, the look in that architect’s eyes. I feel half ashamed that we’ve let that idealism slip away so cheaply, that these consumer cities are the best we can do. But I also feel inspired. Here is proof, concrete proof, that big ideas can happen. That once upon a time, instead of The Gherkin and The Beetham Tower, our cities were building their own icons, for their own people. World-class architecture for old ladies to live in, for young lovers to meet in, for children to cycle their bikes around.

There’s no reason we can’t do it again. Build progressive cities, try to address the problems we’ve created. All we need to do is decide we want to do it. Create our own vision of what the city could be, and challenge our leaders to intervene again, to build green buildings, beautiful markets, new tramlines that we run, that we own. And if our leaders won’t do it for us, we’ll have to find new ones, or, better yet, do it ourselves.

Park Hill is still sitting there, still on the hillside. It still looks beautiful, reflecting the glow of the sunset at the end of the day like an electric fire. Half empty, half gutted, it too is being regenerated, with new windows, new aluminium panels, sexy kitchens and a good dose of hype. It’s going to be a mix of people this time, two-thirds private housing, one-third social. I just hope that, by the time it’s finished, our cities might have got their confidence back, started dreaming again, their own dreams. So that Park Hill isn’t seen as a mistake anymore, but as a legacy, an achievement. A promise to the future.